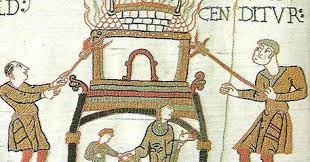

Old Sarum is an iron age hill fort, dating back to c400 BC, that was the original site of what later became Salisbury. It was continuously occupied during the Roman period and a mint was recorded there in 1003. Its original cathedral was built shortly after the Norman invasion of England, as was a motte-and-bailey castle. It was at the latter that the Bastard gathered his nobles in 1086 to swear the Oath of Sarum, a loyalty oath which centralised power in his hands that had previously been delegated to local reeves.

According to legend, the site of the cathedral was moved in 1220 to another one two miles away after an archer shot an arrow into the valley to determine where it should be built. Two miles seems a long way to shoot an arrow, but one variation of the legend is that the archer hit a deer which then ran for that distance before finally expiring.

The Norman castle remained in use until the 15th century, after which Old Sarum was largely abandoned in favour of the newer town. It continued to send members to Parliament until the Reform Act of 1832, however, one of two so-called “rotten boroughs” in Wessex (the other being Newtown on the Isle of Wight).

Today, Old Sarum is maintained by English Heritage. Advance booking is recommended, via their website.