One of the most common criticisms of the modern Wessex movement is that “Wessex doesn’t exist any more.” It is true that Wessex no longer exists as a nation, or as an administrative unit; but as a country of the mind, it has far more power than the government’s South West or South East regions. The title of this post is taken from a description by Thomas Hardy of his literary Wessex, and while Hardy was not the first to revive the name of Wessex in the modern era, he was the first to really popularise it. He later lamented that “I did not anticipate that this application of the word to a modern use would extend outside the chapters of my own chronicles. But the name was soon taken up elsewhere as a local designation. The first to do so was the now defunct Examiner, which, in the impression bearing date July 15, 1876, entitled one of its articles The Wessex Labourer, the article turning out to be no dissertation on farming during the Heptarchy, but on the modern peasant of the south-west counties, and his presentation in these stories. Since then the appellation which I had thought to reserve to the horizons and landscapes of a merely realistic dream-country, has become more and more popular as a practical definition; and the dream-country has, by degrees, solidified into a utilitarian region which people can go to, take a house in, and write to the papers from.”

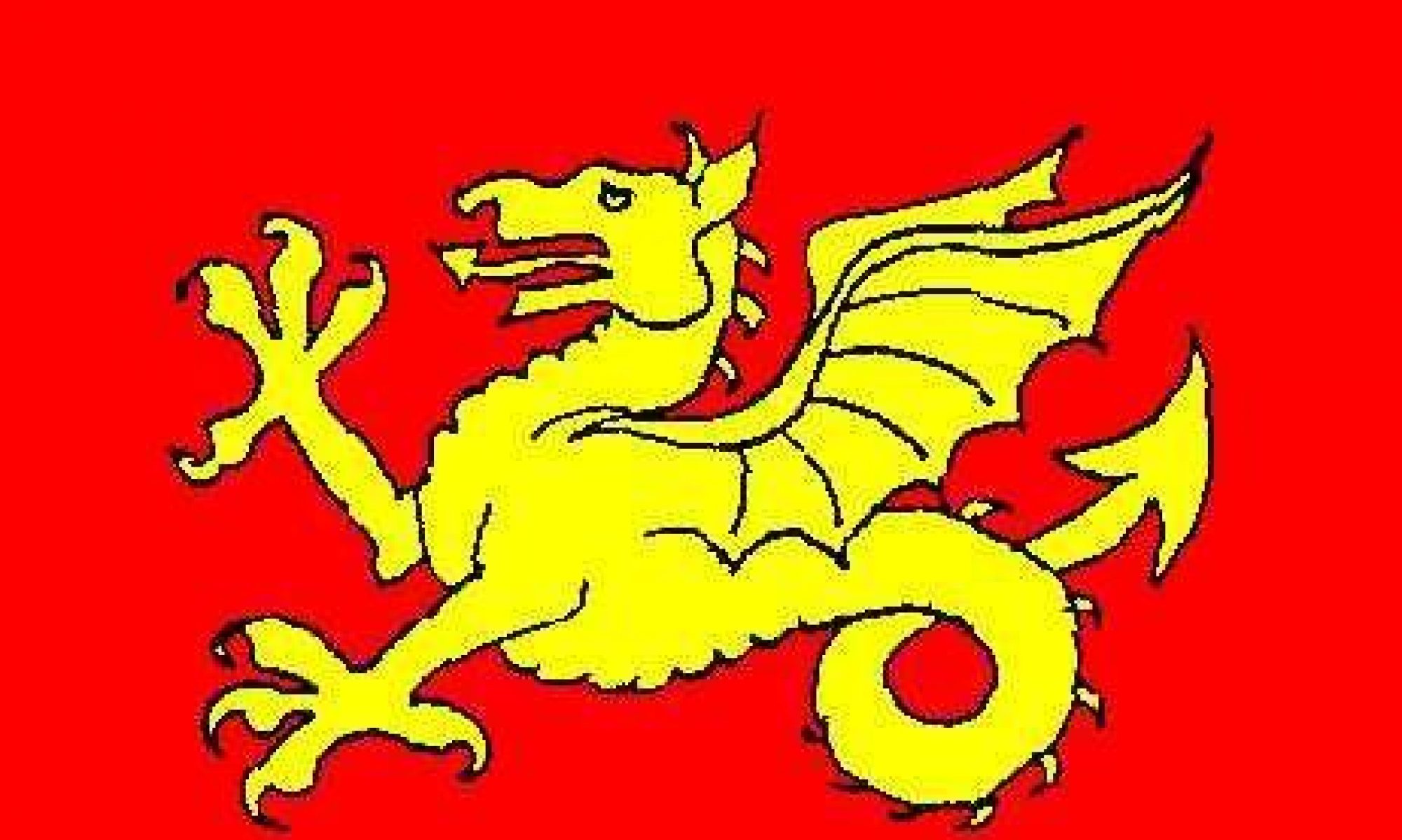

Hardy may not have been happy about it, but it showed that Wessex has an imaginative power that extends beyond his novels and short stories. It is the land of King Alfred and Stonehenge, of cider and chalk figures, Wayland’s Smithy and HMS Victory. But it is also a cohesive modern region. We sometimes attract criticism from historical purists because our definition of Wessex takes modern administrative regions into account, as well as the historical kingdom. Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire were in Mercia, they will say. The Isle of Wight and Meon Valley were Jutish, and Devon was part of Dumnonia. Leaving aside the fact that the borders of historical Wessex fluctuated over time, this somewhat misses the point that we are building a Wessex identity for the 21st century, not the 6th or the 10th century. This is why, while we are critical of the government’s regions when they get things wrong (the “Wessex Iron Curtain” splitting the region in half; treating Cornwall as if it were an English county), we recognise when they get things right (refusing to draw a regional boundary through the middle of Bristol, as Hardy did). Indeed, had the Redcliffe-Maud Report of 1969 recommended the former Southern Economic Planning Region be merged with the South West instead of the South East, there might not be any need for this Society at all. Our work might instead be carried out by a regional Arts Council for Wessex and Cornwall. Whether or not that would be a good thing, I leave you to decide.