This article originally appeared in Wessex Chronicle Volume 17, Issue 1 (Spring 2016)

Wessex Society’s aims, as set out in our constitution, include “promoting Wessex as a cultural community within an English and European context”. The English context should be self-explanatory. The European one comes with the territory; Wessex has been subjected to waves of settlement and conquest from a continent about which it is often ambivalent. From the declaration of the Reformation Parliament that “this realm of England is an Empire” to Shakespeare’s “precious stone set in the silver sea, which serves it in the office of a wall, or as a moat defensive to a house, against the envy of less happier lands”. Viewers of BBC2’s Wolf Hall will know just how many aspects of English politics can be played out on a wider stage. Shakespeare – an English playwright whose plays are mostly set abroad – puts his lines in the mouth of John of Gaunt, an English prince, born in Flanders (at Ghent) and, in his second wife’s right, claimant to the Spanish thrones of Galicia, Castile and León.

Although one might think that nothing could be more English than the Church of England, it was founded by an Italian – Augustine – and revitalised by a Greek – Theodore of Tarsus. The English gave as good as they got: the Apostle of the West Saxons, Birinus was a Frank, while the Apostle of the Germans was an Englishman, Boniface. For us, the Saxons are English: it could be said that they are us. For the Germans, Saxony is an element in the name of three of its regional states and it was the Saxons who went east to settle lands beyond the Elbe. The word for ‘German’ is saksa in Estonian and saksan in Finnish. King Alfred’s name is shared with characters as diverse as Alfred Nobel, the Swedish arms magnate, and Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish French officer falsely accused of espionage. England has a long history of welcoming political outcasts, from Karl Marx to Napoléon III (who is buried at Farnborough Abbey), but the tide flows both ways, taking many a disgraced sovereign or nobleman to France or the Low Countries.

So here’s a question: how many members of the European Union can claim a constitutional link to England? The answer may be surprising: 14 out of 28. The figure is calculated as follows.

1. States that are, or have been, part of the UK number 2: the republic of Ireland (1801-1922) and the continuing United Kingdom. The UK for this purpose includes Gibraltar, which is not represented at Westminster but is represented in the European Parliament as part of the ‘South West England’ constituency. The Channel Islands and the Isle of Man are Crown dependencies, for most purposes outside both the UK and the EU. The Channel Islands are the last remaining fragment of the Duchy of Normandy; during the Commonwealth period they narrowly avoided incorporation into Hampshire. They have been part of the diocese of Winchester since 1569, though an acrimonious split in 2014 resulted in the Bishop handing many of his powers up the line to Canterbury.

2. States that have been part of the British Empire, while not being part of the UK, also number 2: Cyprus (1878-1960) and Malta (1800-1964). Running total 4.

3. States whose territory includes territory that at one time was English or British number 4: France (a bloc from Normandy to Aquitaine, begun 1066, the last part lost 1453, also Ponthieu, 1279-1435, Calais, 1347-1558, Dunkirk, 1659-1662, and Corsica, 1794-1796), Germany (Heligoland, 1807-1890), Greece (Ionian Islands, 1809-1864) and Spain (Minorca, 1708-1802). Running total 8.

4. States that have shared a monarch with England, Great Britain or the UK, or include territory that has done so, number 6+: Denmark (1013-1042), France (1422-1435, contested by the Valois), Germany (Hanover, 1714-1837), the Netherlands (1689-1702), Spain (whose empire at the time included some or all of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, 1554-1558) and Sweden (Scania, then part of Denmark, 1013-1042). Running total 14. Norway (1013-1035) would also feature in the list if it were a member of the EU.

Eastern Europe is poorly represented in this list, though English connections through marriage do exist: King Athelstan’s half-sister married the German Emperor Otto I and is buried at Magdeburg, Edgar Atheling’s mother was possibly Hungarian or Russian, and Harold Godwinesson’s daughter married the Grand Prince of Kiev. Richard II renewed the connection with central Europe, marrying Anne of Bohemia. One consequence was to forge links between England’s emergent Lollards, strong in mid-Wessex, and Bohemia, where they were known as Hussites.

Cardinal Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester was Papal Legate for Germany, Hungary and Bohemia and led the struggle against the Hussites. Beaufort also played a large role in the Hundred Years War, being present at the trial of Joan of Arc. (He came home with her ring, which only returned to France this year when it was sold at auction to a historical theme park after centuries of English aristocratic ownership.) Beaufort also served as Dean of Wells, Chancellor of Oxford University and Bishop of Lincoln (the city to which the see of Dorchester-on-Thames was removed in 1072). And where was he born? France, as the son of ‘Old John of Gaunt, time-honour’d Lancaster’, by Chaucer’s sister-in-law, and so a cousin of Richard II. Confused yet?

You might think that Wessex, as close to the continent as it is, would bear some signs of these varied constitutional tie-ups, and you would be right. The story begins with Cnut, King of Denmark, England and Norway, who died in 1035 and was buried in Winchester Cathedral. His name appears on the mortuary chests there. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 1029, “King Cnut returned home to England”: as good an indication as any of where his primary interests lay.

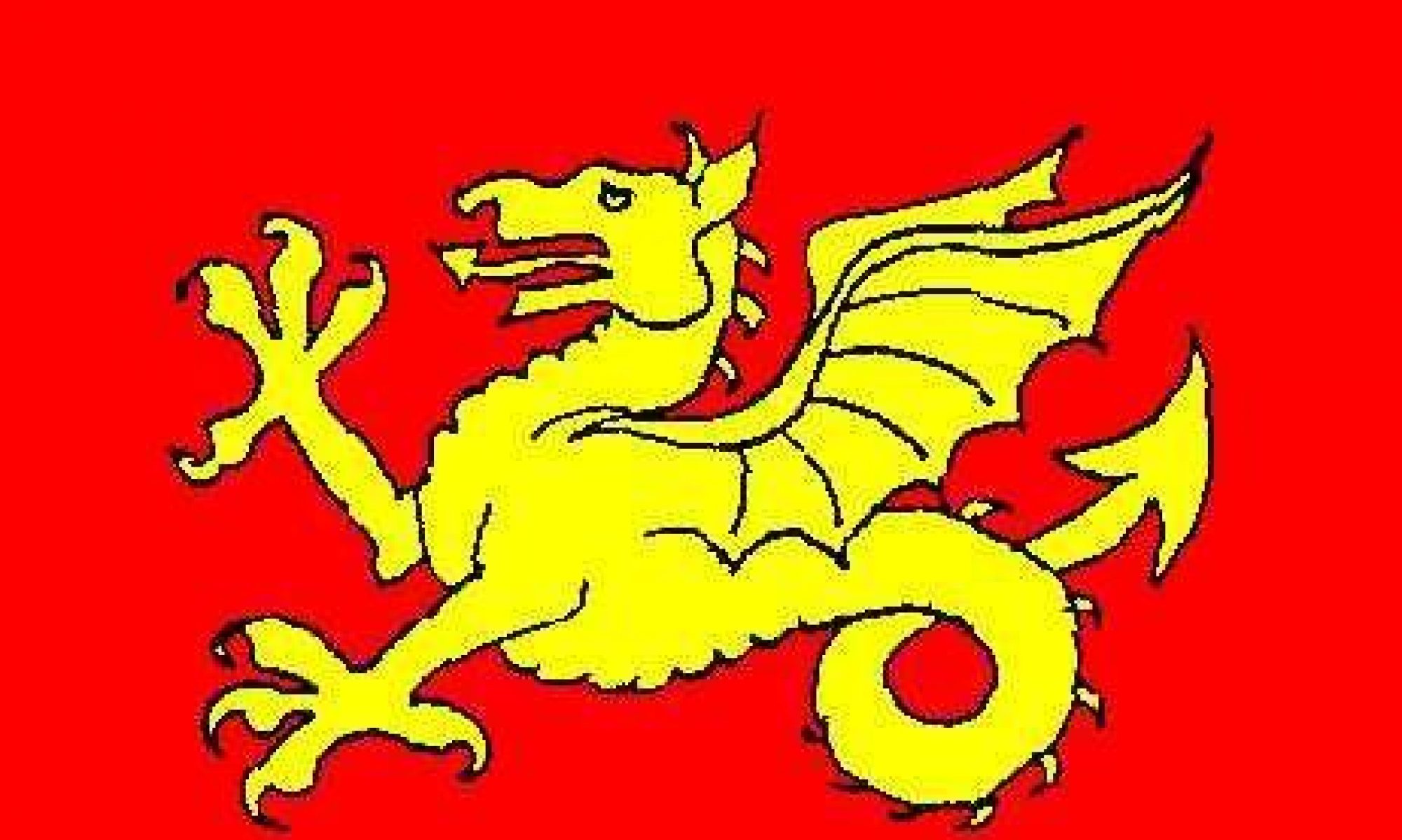

We have mentioned before King Louis of England, a little-known monarch who occupied London and Winchester in the dying days of King John. King Philip is another little-known monarch. The man we know as the Spanish king Philip II married Queen Mary I – ‘Bloody Mary’ – at Winchester Cathedral in 1554. Why Winchester? Probably as the nearest large church to Southampton, to which he could swiftly beat a retreat if things turned nasty. Parliament was greatly concerned that the marriage should be merely personal and not give Philip any claim to the English throne after Mary’s death. (The Spanish Armada of 1588 was Philip’s bid to enforce a separate claim bequeathed by Mary, Queen of Scots.) Despite these safeguards, the official line at the time was that a new, joint reign had begun. Philip and Mary appeared together on the new coinage. The new Great Seal bore their combined coat-of-arms, which featured the English lion as one supporter and the black imperial eagle as the other, displacing the red dragon of the Tudors. The citation of Parliamentary statutes began afresh, the year ‘2 Mary’ being followed by ‘1 & 2 Philip & Mary’. The rulers were proclaimed jointly as ‘Philip and Mary, by the Grace of God, King and Queen of England and France, Naples, Jerusalem and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant’. (Philip did not ascend the Spanish throne until 1556.)

Some of these titles were just delusional. England had no territory in France except Calais, which was represented in at least ten English Parliaments at Westminster but which Mary was famously to lose. The Kingdom of Jerusalem had lost Jerusalem itself in 1187 and its last possessions in 1291. The Duchy of Burgundy had been taken back by the King of France in 1477. The claims are worth noting as a demon-stration that history is about editing-in and editing-out, with perspective determining the choices to be made about breadth and depth: to tell us our past, it has to know who ‘we’ are. Louis and Philip were real English monarchs but, like Edgar Atheling (or Edgar II) in 1066, they don’t appear in our king-lists because history is written by the victors. And our own Henry VI was crowned Henri II of France in 1431 – by Cardinal Beaufort no less – but thanks to the example of Joan of Arc he doesn’t count either.

We’re equally selective about invasions, William the Bastard’s being often referred to as the last successful one. In 1688, William of Orange turned up in Brixham with 15,000 Dutch troops and over the next few weeks marched across Wessex to Windsor before being crowned king. That looks very much like an invasion and very much like success. To redefine the Norman Conquest as the last successful opposed invasion is one way out: but only because in 1688 the opposition wasn’t coming from those who had invited the Dutch over. The incumbent king, James II, wasn’t at all in favour of the coup and doubtless would have opposed it if he could.

William of Orange, like Cnut, chose to live and die in England, not in his home country. George I was the opposite, a thorough-going German and the last ruler of England not to be buried in England, but his family’s English connections went back a long way. His ancestor Matilda of England was the daughter of Henry II; one of her sons by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, was William of Winchester, born there in 1184. William, also known as William of Lüneburg, was born during his father’s exile in England. He remained there when his father returned to Saxony and was raised in the court of Richard I. (That’s Richard the Lionheart, the king married in Cyprus to a Navarrese who never visited England as queen.) His dynasty continued to reign in north-west Germany until 1918. Its impact on English life can be seen in the numerous streets and squares named ‘Brunswick’ or ‘Hanover’. The last King of Hanover, its George V, was baptised in Berlin by Jane Austen’s brother, the Rev. Henry Thomas Austen, and is buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor. The British returned to Hanover in 1945 with an army of occupation, while the USA occupied the south of Germany. It could not have been otherwise: D-Day was launched with the Americans on the right flank because that was where they had been gathered from the UK’s Atlantic ports and logistically they had to end up on the right flank too.

During the personal union of Great Britain/the UK and Hanover under the first four Georges and William IV, the smaller country could sometimes be the tail wagging the dog. The Elector of Hanover was so-called because he was one of nine princes called upon to choose the next Holy Roman Emperor (a contest that the Habsburgs hardly ever lost). He also got to use the title of Arch-Treasurer of the Empire and incorporate a representation of the crown of Charlemagne into his coat-of-arms, something that can be seen in the British royal arms of the time. The same arms adorn the pediment of the parliament building of Lower Saxony in Hanover.

British troops were deployed in the defence of Hanover, while Hanoverian regiments were raised for British service, being known as the King’s German Legion. Thomas Hardy’s 1889 short story, The Melancholy Hussar of the German Legion, recounts the fate of two soldiers based at Weymouth who are shot for desertion. One is a native of the Saarland and the other of Alsace.

In The Return of the Native, Hardy created another foreign character to place in South Wessex. Of Eustacia Vye he writes: “Budmouth was her native place, a fashionable seaside resort at that date. She was the daughter of the bandmaster of a regiment which had been quartered there – a Corfiote by birth… Where did her dignity come from? By a latent vein from Alcinous’ line, her father hailing from Phaeacia’s isle?” A Corfiote being a native of Corfu, one of the Ionian Islands, he may be assumed to have played in a military band during the time of British rule. One of the relics of that rule is the Order of St Michael and St George. It was created as an award for British subjects in the Ionian Islands and in Malta but is today better known as the ‘gong’ given to senior diplomats and civil servants in the UK, ranked in its three grades of Companion (CMG: ‘Call Me God’), Knight Commander (KCMG: ‘Kindly Call Me God’) and Knight Grand Cross (GCMG: ‘God Calls Me God’).

Does this trans-European history still echo today? The best place to look is in town-twinning arrangements, some of which might be seen as predictable. Bristol is twinned with Bordeaux, the capital of Aquitaine, and with Hanover. Bath is twinned with Brunswick. Several counties are twinned with Norman equivalents: Devon with Calvados, Dorset with Manche, Somerset with Orne, and Hampshire with the whole of Lower Normandy (all three of these départements together). As Upper and Lower Normandy have just been re-united, will Hampshire now try to speak for all Wessex or see itself alone as the equal of all Normandy? That will be interesting to watch. Berkshire and Wiltshire are twinned with the Vienne and Loiret départements in Poitou and central France respectively. Port towns are easily paired: Plymouth/Brest, Poole/Cherbourg, Southampton/Le Havre, Portsmouth/Caen. Romsey’s twinning is with Battenberg, the original home of the Mountbatten family. Winchester’s is with Laon, the former capital of France. Oxford is twinned with a clutch of university towns. Wincanton is twinned with the fictional town of Ankh-Morpork in the late Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld – and Swindon with Walt Disney World in Florida. Magic.